Where we are

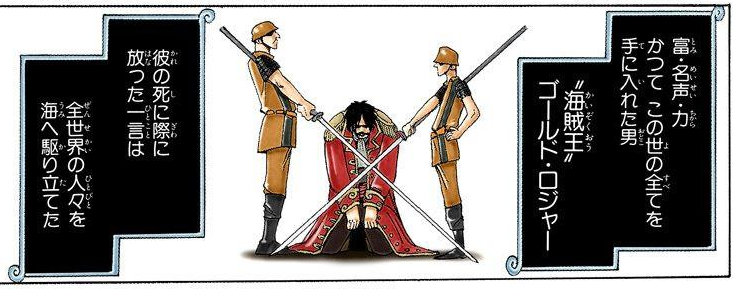

In the previous posts, we translated a presentation from the narrator, presenting Gold Roger, the king of the pirates who obtained everything this world has to offer.

Let’s check how it goes on!

This is a bit long sentence! Let’s first write it from left to right:

That reads:

kare no shinigiwa ni hanatta hitokoto wa zensekai no hitobito o umi e karitateta

Let’s do the logical analysis of the sentence, from left to right

彼の (kare no)

The first part of the sentence is composed by the pronoun “kare” and the particle “no”.

彼 means “he”, and it’s composed by the parts 彳(step) and 皮 (pelt). You can imagine a paleolithic man going around with pelt clothes to remember it!

We already saw the particle “no”: this is the possesive case and it means that next in the sentence we’ll find something that belongs to “him”

死に際に (shinigiwa ni)

You may already saw the first kanji somewhere: 死 means death. This has a strange story attached. Even if the bigger parts are 歹 (bare bone) and 匕 (spoon), we can split the first part even further to obtain 一 (one) and 夕 (evening). So.. One evening, I choke to death because of a spoon. Very sad, but now I can remember the kanji!

The second kanji is 際, which means “occasion, side, edge”. This is a bit complicated, composed by 阝(mound, dam), 癶 (dotted tent) and 示 (show, indicate). I haven’t found a satisfying story yet, so feel free to make up one!

Now, for the particles. The first one marks “death” as the “place” that “occasion, side, edge” refers to. So, it means something like “on the point of (his) death”.

The second ni marks the whole expression as another “place” referred to the next words, so we could translate the sentence until now as: at the point of his death…

放った一言は (hanatta hitokoto wa)

I put this part of the sentence together, because the verb used here may be a little ambiguous without knowing the context.

The verb here is 放った (hanatta). The kanji means “set free, release, fire, shoot, emit, banish, liberate…” a lot! It’s very hard to say what it should mean without context. Its parts are 方 (direction, person) and 攵 (strike, hit). So when you are completely free, you can strike in any direction!

Another thing we know from this word is that it is conjugated in paste tense. But what is this verb referring to?

一言 (hitokoto) is another phrase composed by two words that we already saw (I think): one 一 and word 言. You may think this means “one word”, but it also can mean “few words”. Now it’s more clear what is it that we “set free” or “shoot”: words.

The sentence then is: “The words he said at the point of his death…”

Then we have the は particle (which is the hiragana for HA, but it’s read as WA when used as a particle!). This particle tells us that what we have before it is the topic of the sentence. Note that this is not always also the subject!

So, the words the pirate king said before dying are the topic of what comes next in the sentence

全世界の (zensekai no)

Let’s take aside the sentence until now and start again as if this was a new sentence.

We already saw the first kanji in the previous post: 全 means “all” and it was used in 全て (subete) to mean “everything”. In this case it’s read “zen”, but the meaning is the same: whole, all, everything.

We already saw also the second kanji, 世 with the meaning of “world”, and it was read as “yo”. In this case, 世界 (sekai) still means “world”, but in a more physical way. Meaning, you can use 世 (yo) to refer to our world, to the spirit world, to a parallel world.. but 世界 (sekai) strictly means our physical world. The second kanji, 界, composed by a rice field with some strokes below, represents and means “border”. So we can imagine why the sense of 世 is reduced to only our tangible world when they are used together!

At the end, just like the other parts, the particle の tells us that we are talking about something that belongs to our world

人々を

The kanji 人 means “person”. Simply as that, there’s no trick or radical to remember it, it’s so simple that you can just learn it as is 🙂

The second kanji doesn’t have his own meaning, it’s just used to symbolize the previous kanji written two times. Instead of writing 人人 we write 人々 to form a sort of plural. Notice that this duplication alters a bit the reading of the kanji! Instead of HITOHITO we read it as HITOBITO.

So, the sentence until now means “people all around the world”. Since now we have the を particle, these people are the object of the next verb

海へ (umi e)

We also already saw this kanji: 海 means sea! In this case we have the へ particle, which is read “he” in hiragana, but “e” when it’s used as a particle. This means “in the direction of”, so we could say this is a complement of motion to place. Now we just need the verb to put everything together

駆り立てた (karitateta)

駆 means “drive, run”. It is composed by 馬 (horse) and 区 (ward). We can remember it with the story: In this ward of Japan, you can only drive on horses.

Also in this case the verb is in past tense. We don’t have an explicit subject, so the topic of the sentence will also be the subject in this case.

Summing everything together, we can translate it as:

The words he said before his death drove to the sea the people of the whole world!

I hope everything is clear and I did not make mistakes 🙂 See you in the next translation episode!